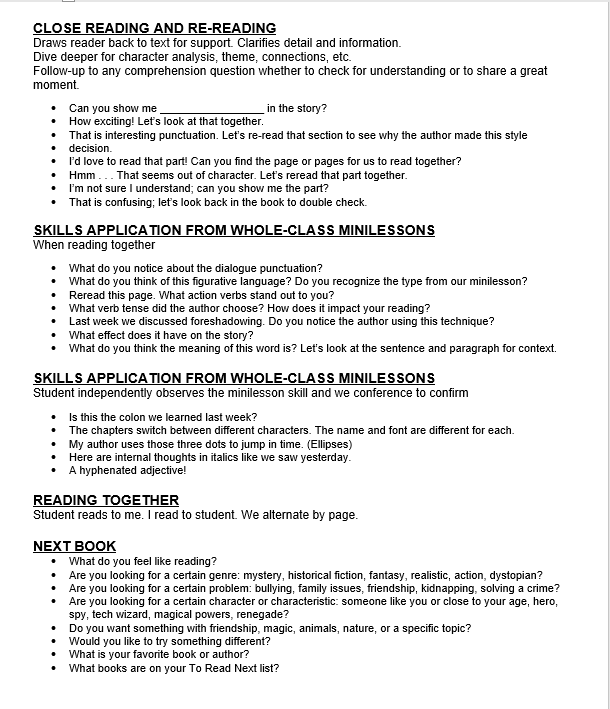

Prompt-ober: Short Stories as Writing Prompts

Nearing the end of October, when the leaves shift hues, the temperature dips, and Halloween dances in the near future, the students of room 294 venture into the haunting short story, “The Landlady” by Roald Dahl. This is the perfect story to revitalize our energy, coming fresh off our memoir unit, and to continue the practice of sensory details and imagery in writing.

Throughout Roald Dahl’s famous piece, images and details such as “paint was peeling from the woodwork,” and “She had a round pink face and very gentle blue eyes” cover the pages. One of Dahl’s most detailed descriptions occurs when the main character, Billy, peers into the window of the Bed and Breakfast:

“Billy caught sight of a printed notice propped up against the glass in one of the upper panes. It said BED AND BREAKFAST. There was a vase of yellow chrysanthemums, tall and beautiful, standing just underneath the notice . . . Green curtains (some sort of velvety material) were hanging down on either side of the window. The chrysanthemums looked wonderful beside them. He went right up and peered through the glass into the room, and the first thing he saw was a bright fire burning in the hearth. On the carpet in front of the fire, a pretty little dachshund was curled up asleep with its nose tucked into its belly” (Dahl).

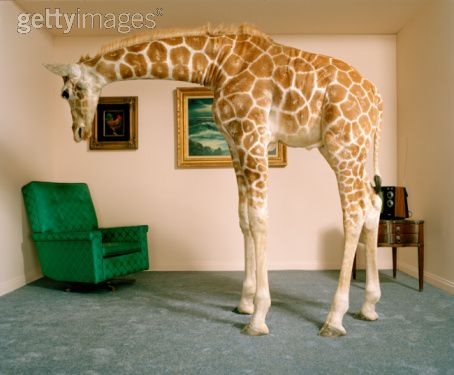

During class, a discussion on the use of details and imagery that Dahl utilizes in creating this passage ensues. After some time, the students sketch and color their depiction of this room. From here, we use Dahl’s passage as a model to create our own descriptions of a window we are “peeking in.” In the student’s Google Classrooms, I post about fourteen different photos of unique and colorful rooms (as seen below).

After the students have taken some time viewing the various images, they choose their favorite photo and write a passage to describe the room, just as Roald Dahl in “The Landlady.” The key to this prompt is adding details and imagery. The end result is wonderfully descriptive passages that further emphasize and practice the use of sensory details and imagery in writing.

“A Giraffe stood in the middle of a tiny room, too tall for his own good. His neck bent at a 90 degree angle with his front feet. The giraffe stood on a worn out turquoise rug, that covered the whole ground. The walls glowed a beautiful tan, with pictures framed with gold along the back side. A green silky chair lay aloft the ground in the back left corner. The chair has an intricate design, with x’s stitched across the whole surface. In the bottom right corner, adjacent to the chair, stood a brittle old table, with four drawers that curved like a wave. An old time radio stands tall on top of the table. The giraffe has blobs of brown, that lay upon the white fur of the giraffe. Although the giraffe doesn’t stand tall, the hair on the back of its neck stands tall. Imprints of feet align the floor, turning the worn out turquoise rug into a white one. The phrase Getty images is what it said in the top left corner, in a white color and big font.” –Period 7 Student

Jasmin is a writer this year who immediately drew on her strengths to tell her experience of writing: “I’m a writer when I feel as though the story has to be told. The way I want the story to be told is most important.” She took the opportunity to look at herself

Jasmin is a writer this year who immediately drew on her strengths to tell her experience of writing: “I’m a writer when I feel as though the story has to be told. The way I want the story to be told is most important.” She took the opportunity to look at herself