You’re Cordially Invited: Design Your Personalized English Teacher Summer Camp

“PAWLP’s Invitational Writing Institute is summer camp for English teachers!”

I made this declaration the second week of my institute in 2017—and I meant every word of it. The institute revealed how much I missed immersing myself in reading, writing, and researching.

The last two summers, I have designed my own independent writing institute of sorts. I set goals and outlined “assignments” to complete. I collected texts and ideas as I went, joining book clubs, connecting with colleagues, presenting, and establishing writing and reading routines.

For this summer, I am in the process of creating a personalized summer camp syllabus to guide my creative and professional exploration. Here is what I have so far:

1. Creative Writing and Writing Process Reflections

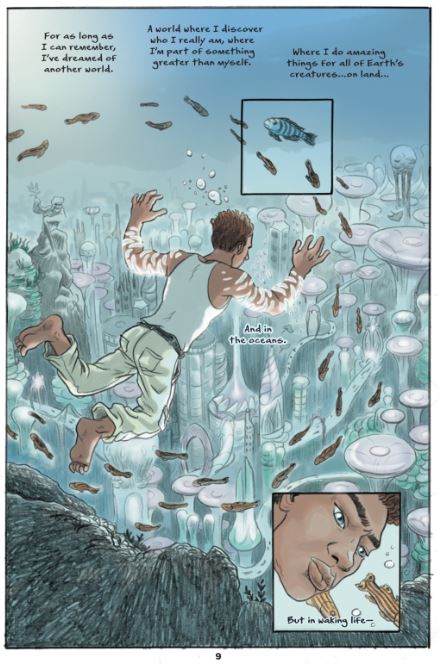

After the institute, I started to use the quick write time with my students to focus in on my creative writing interests. Before, my notebooks were filled with random ideas, inspired by the quick write’s topic of inspiration. Instead, I began to focus on my creative interests and love of dystopian and sci-fi stories. As I generated ideas based on genre and craft, a storyline and character started to take shape. The more I stuck with this inspiration, the more the idea developed. I shared and shaped my ideas with students, family, and friends. Not only did this experience enhance my own writing process, but also I was able to talk to my students about how they might use quick writing to focus on specific interests of theirs or to develop their Self-Selected Writing pieces. Although I had suggested this in the past, I started to nudge students more. Now, I am nudging myself to complete a messy first draft by the start of the school year.

My colleague at Lenape Middle School, Christy Venters, and I will be hosting Lenape’s first virtual Reading-Writing Summer Club, starting next week. We are excited to support our students’ reading and writing as well as offer some much needed socializing since many of them are still feeling the isolation of social distancing. I am also looking forward to sharing my work and receiving feedback.

Although I have always been a reflector and instilled this in my students with metacognitive reflections, my spring 2020 grad class, Composing in the Attention Economy, with Dr. Famiglietti pushed me to take my thinking further. After discussing options for the scope of my web presence assignment, Dr. Famiglietti suggested creating a blog that focused on my writing process. It has been a fun and eye-opening experience, pushing me to get into the trenches of my thinking and writing process. Over the summer, I will continue posting at least once a week.

- Is there a creative or personal writing project you started but have not finished or have wanted to start but have not found the time?

- What is holding you back?

I have always found that summer is a great way to jump into a project and nurture that creative side!

2. Research Interests

For this summer, I want to touch on the following research interests:

- Creating student leaders within the writing-reading workshop

- New teacher mentoring frameworks and pre-service programs

- Digitizing the writing-reading workshop

I’ll spend time over the summer reading and studying books, articles, and studies. I’ll explore best practices and ways to re-imagine those best practices. And, I’ll pick a few ideas to write about whether for personal reflection, PAWLP blog articles, or posts on Yammer. I will check out the call for manuscripts for NCTE, CEL, NJCTE, PA Reads, The Amplifier Magazine, and other professional journals and organizations. Regardless of whether I submit or write a completed draft for any of these calls, the ideas will help me consider how I might enter into these academic conversations now or later.

Additionally, I will be gearing up to write my master’s thesis in the next year. I will use this summer and my research interests to focus in on my ideas and decide what avenue I would like to explore.

- What do you want to learn more about?

- What would you like to re-visit or investigate further?

- How might researching your interests guide you to implement action research next school year?

3. Next/Best Practices

Two focus areas for me to hone this summer and put into practice next year will be utilizing Canvas and Teams to enhance distance learning and celebrating diversity through multicultural literature.

The two books that are starting out my inquiry on distance learning are Catlin Tucker’s Blended Learning in Grades 4–12 and Karen Costa’s 99 Tips for Creating Simple and Sustainable Educational Videos. I will consider how I can best use Canvas and Microsoft Teams to enhance distance learning, the balance of asynchronous and synchronous learning, and the social and collaborative opportunities for students.

To investigate how to further foster diversity through multicultural literature in my classroom, I am in the process of collecting books and articles that will drive my inquiry. I will reread Sara K. Ahmed’s Being the Change and Tanu Wakefield’s article “The ‘Close Reading’ of Multicultural Literature Expands Racial Literacy, Stanford Scholar Says”, and I will study Mathew R. Kay’s Not Light, But Fire. These along with other resources will ask me to reflect on the books my students have access to, the titles we book talk, and the whole-class and book club novels we read. They will help me to offer a variety of multicultural books, lead meaningful conversations, and invite students to expand on their thinking and world perspective.

- What is something new you want to try out or feel is important to try out in your classroom?

- What practices do you want to re-examine, re-study, or re-imagine?

- How will investigating a topic or topics enhance your teaching philosophy and improve your students experience for the 2020-2021 school year?

I am looking forward to a balance of relaxation and rejuvenation this July and August. Between spending time outside, social distancing with family and friends, and attending my personalized summer camp, I know summer 2020 is going to be great.

If you have not participated in an Invitational Writing Institute, please treat yourself and sign up for summer 2021! This was one of my favorite professional experiences!