Creativity in the Classroom

This is a question that has influenced my teaching for as long as I can remember. Even before I saw the iconic TED Talk by Sir Ken Robinson, I was always trying to think outside of the box with my young, 9th grade students. I’ve waffled back and forth over showing this since it was originally posted in 2006, but it remains the most popular TED Talk, and I see its message as (still) relevant today.

Before Viewing…

I start my students with a “Four Corners” activity. I give them a series of statements all found here and they have to pick a corner representing Agree, Strongly Agree, Disagree, or Strongly Disagree. I’ve witnessed some interesting discussions and I’ve even had to allow students to pick the ‘neutral zone’ of the classroom’s center.

After we do this activity, I tell them we are going to do a little experiment. We are going to take an IQ test. I use one that’s been used by Mensa but I am sure you can find others online. I give them 7 minutes, then I ask them to journal their response to taking this ‘test’. Once we go over the answers, we also engage in a discussion about the inherent biases they observe in the questions themselves. Then, we talk about how this particular tool did/didn’t measure their intelligence.

As a follow up, we then do a Multiple Intelligences Assessment created by Howard Gardner at Harvard’s Project Zero. We follow the same protocol: timed, reflection/writing, discussion. And the students quickly realize that this particular assessment didn’t undermine their intelligence, it just illustrated their strengths and weaknesses.

Communal Viewing

I think there is value in watching this video together. I provide this note sheet for my students but tell them they can also just use their Writer’s Notebook. Then, we watch. Maybe you’ve seen it before, maybe not…I’d love to know.

Post-Viewing

This video inevitably leads to fantastic and passionate conversations in the class. I reveal – at last – the point for my students. They are just heading into their multi-genre research and I want them to feel empowered to pick a topic that inspires them! Of course I give suggestions and show them the wide variety of topics that former students have selected…the point is, write about something you care about. I am not going to kill that creative urge that may be lingering inside of my students.

So, ask yourself, how do YOU cultivate creativity in your classroom?

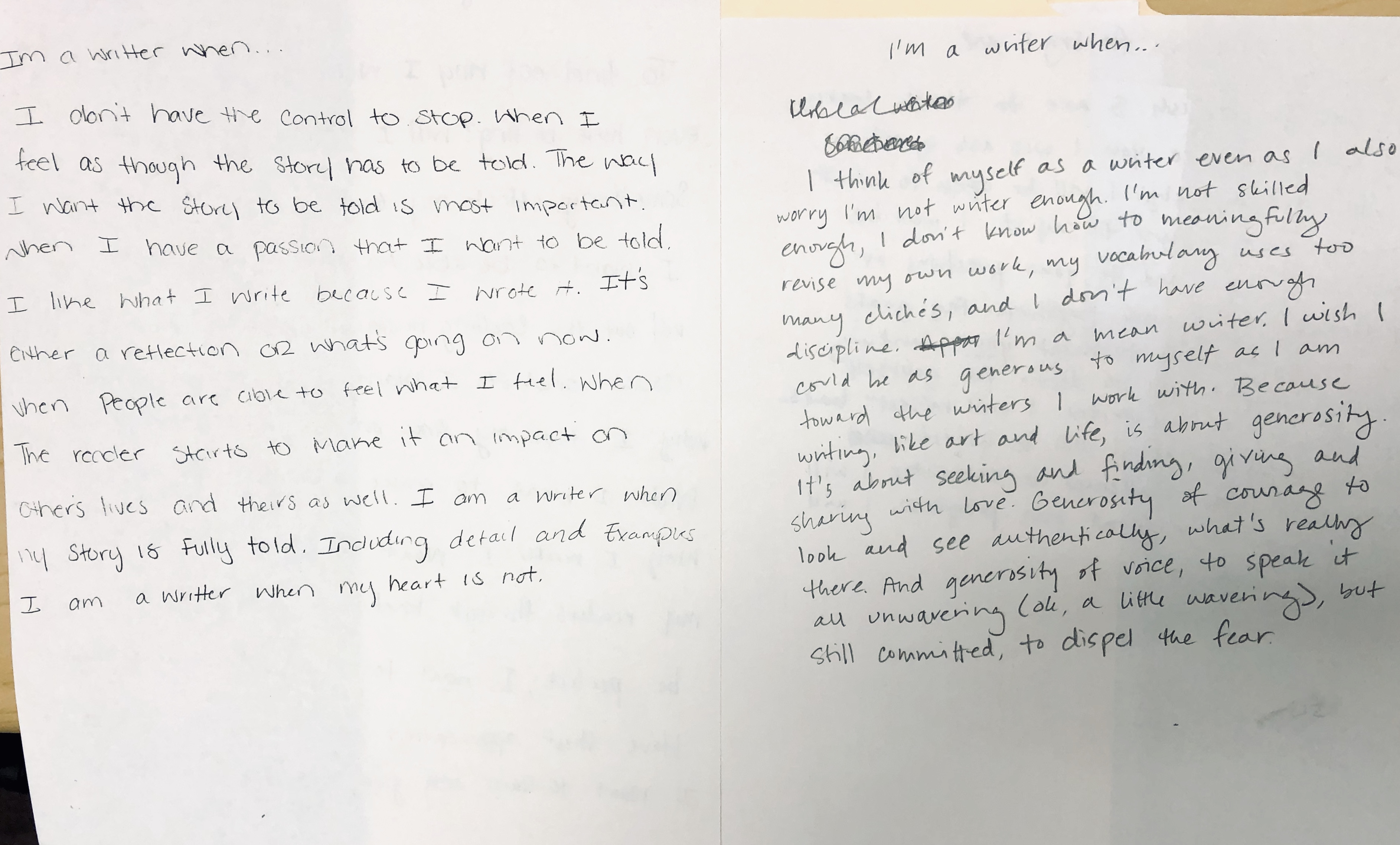

Jasmin is a writer this year who immediately drew on her strengths to tell her experience of writing: “I’m a writer when I feel as though the story has to be told. The way I want the story to be told is most important.” She took the opportunity to look at herself

Jasmin is a writer this year who immediately drew on her strengths to tell her experience of writing: “I’m a writer when I feel as though the story has to be told. The way I want the story to be told is most important.” She took the opportunity to look at herself

After ten minutes, I circled back to Jane.

After ten minutes, I circled back to Jane.