by Heidi Fliegelman

Overview:

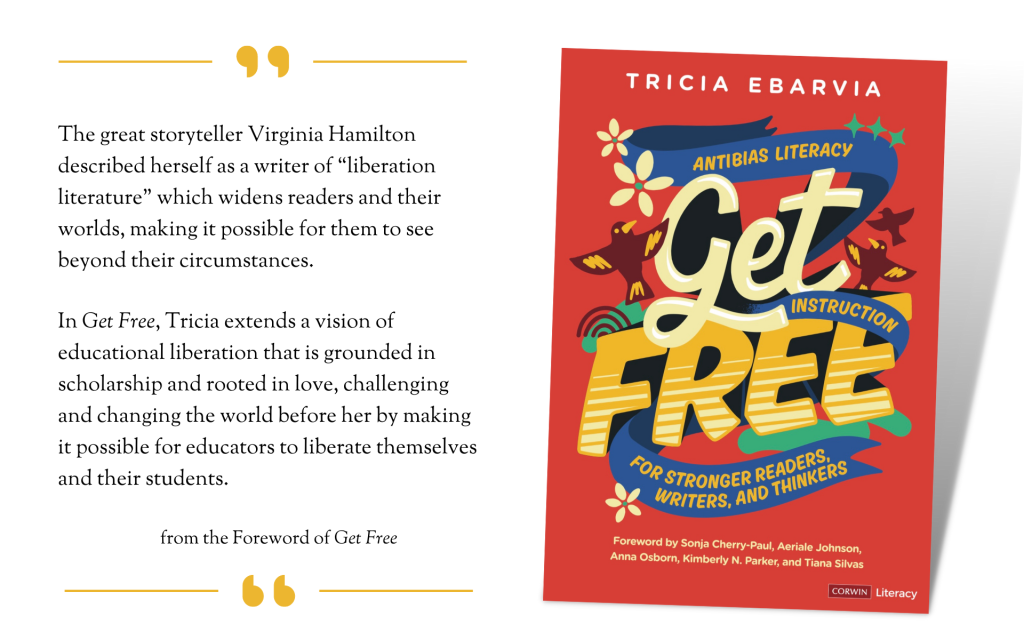

Tricia Ebarvia’s book, Get Free, functions as both an instructional guide and a reflective piece that surrounds the pursuit of equity in education. Across six chapters, the seasoned English Language Arts educator explores what it means to provide a liberatory education for all students. Her combination of anecdotes, research analysis, classroom activities, and student reflections make for a well-rounded, detailed, effective guide.

Chapter Breakdowns:

In her first two chapters, Ebarvia focuses primarily on identity, unpacking how teacher bias and curriculum bias are ingrained and pervasive in the classroom. This begins with a deep dive into her early understanding of what constituted good literature, and how her understanding has changed as her own learning has progressed (2-3). Ebarvia provides a myriad of strategies and reflection questions for educators throughout these chapters, as well as provides anecdotes from her own teaching experiences, and that of her peers. She mentions bias early, outlining the different types that show up specifically in school settings, and providing privilege checklists and other methods of identifying such ideas in our own practice.

For instance, Ebarvia discusses the way in which teacher privilege directly affects how comfortable one might be in discussing difficult conversations in the classroom (15). While having more privileges might make some teachers wary of overstepping in talking about a social group they do not belong to (or, worse, feel as though it’s irrelevant), Ebarvia focuses her analysis elsewhere. Through the anecdote from Wolfe-Rocca, Ebarvia prompts reflection on how yes, while sensitive topics should be discussed and brought forth by those who have the privilege to do so, these topics still need to be handled with care, and encourages teachers not to rush into big conversations– they should be planned, intentional, and empathetic, considering “as teachers, we wield tremendous power in our classrooms” (14). This section closes with Ebarvia asking educators to consider the question: “In what ways do you think your own identities might have affected your interactions with your own students?”, keeping with the earlier emphasis on educators understanding the “I who reads” (4).

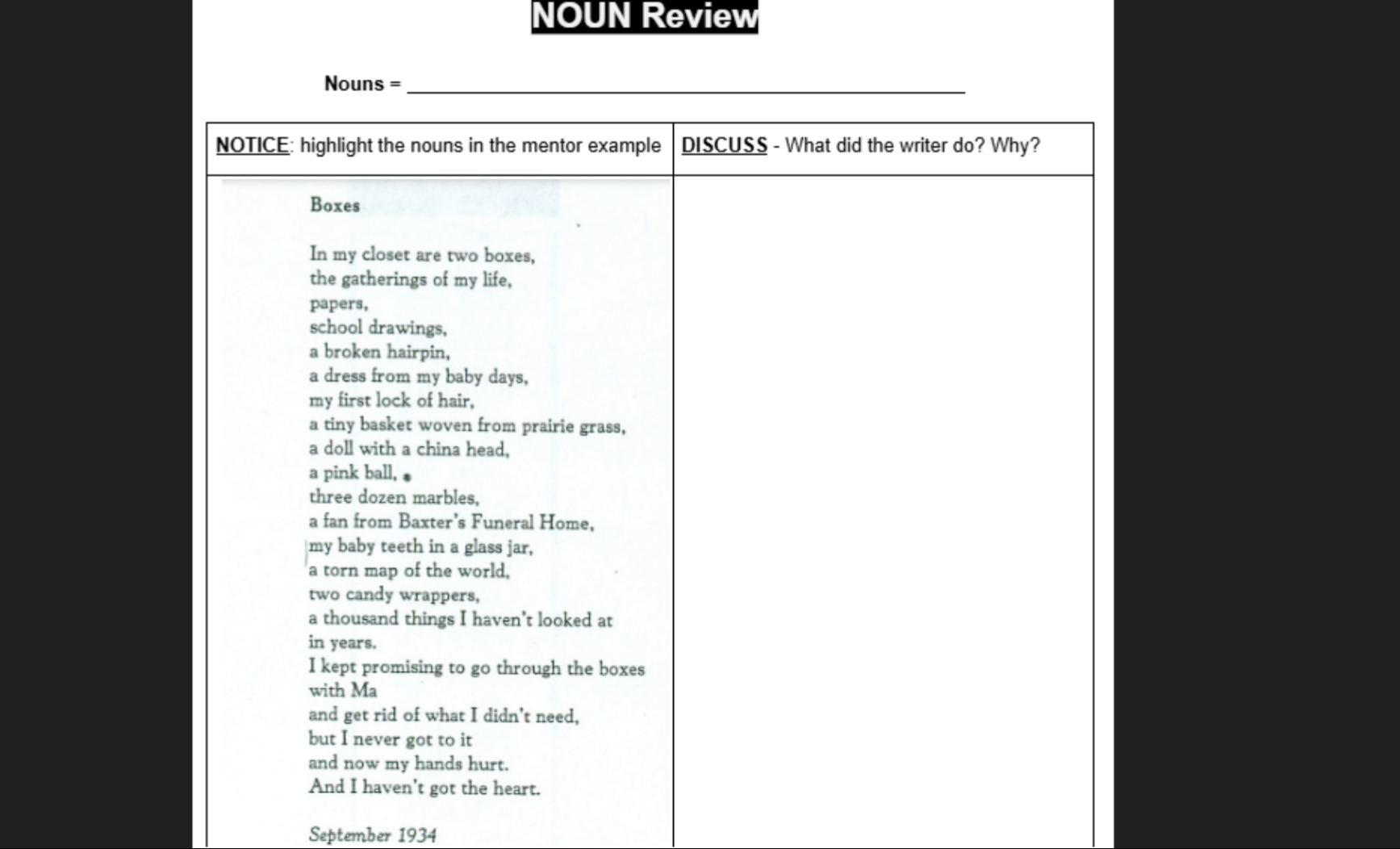

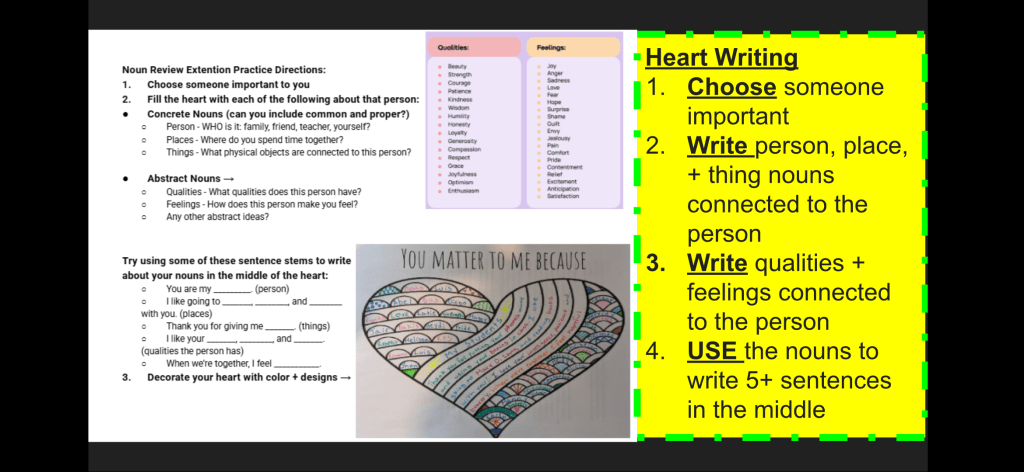

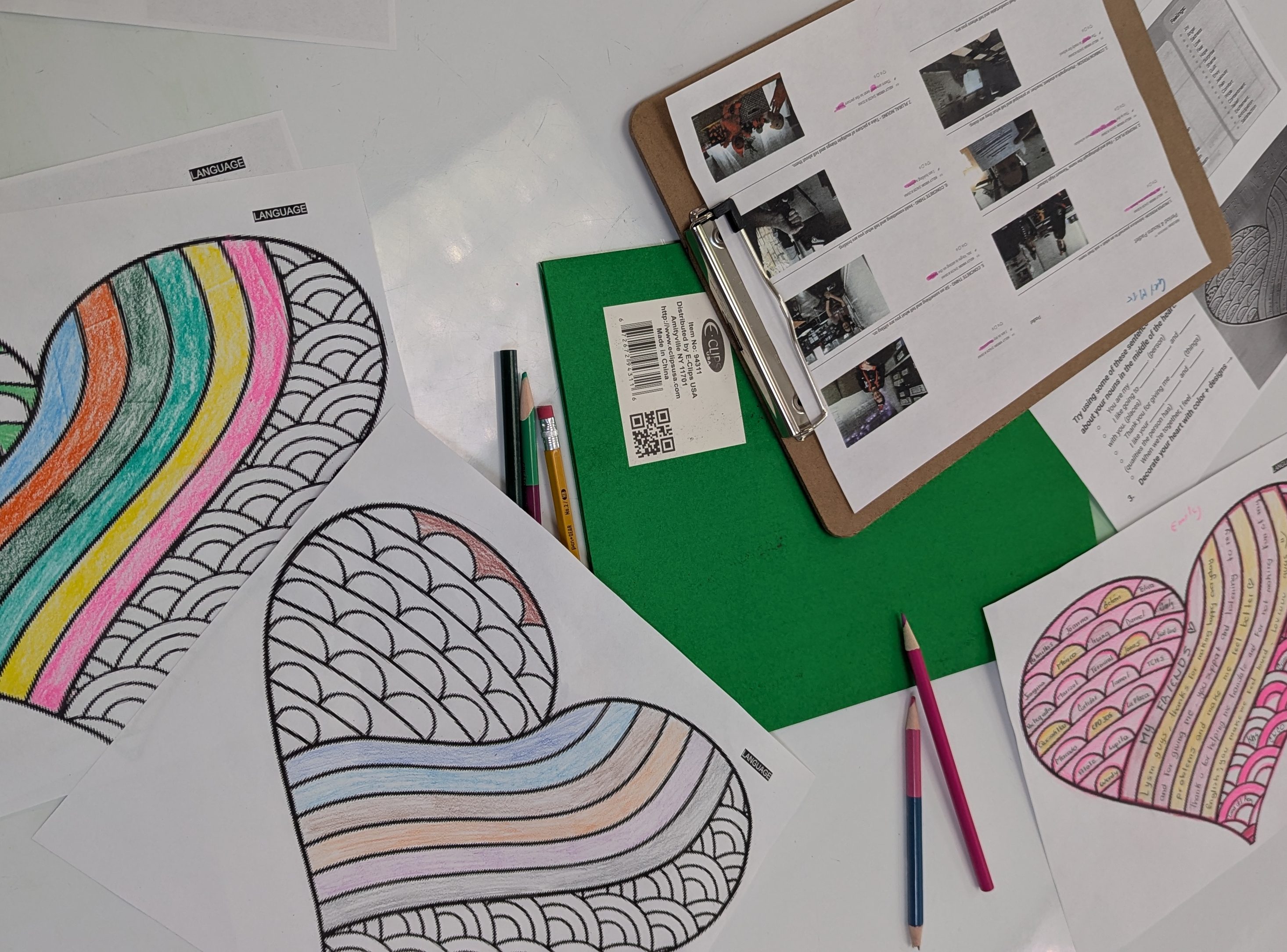

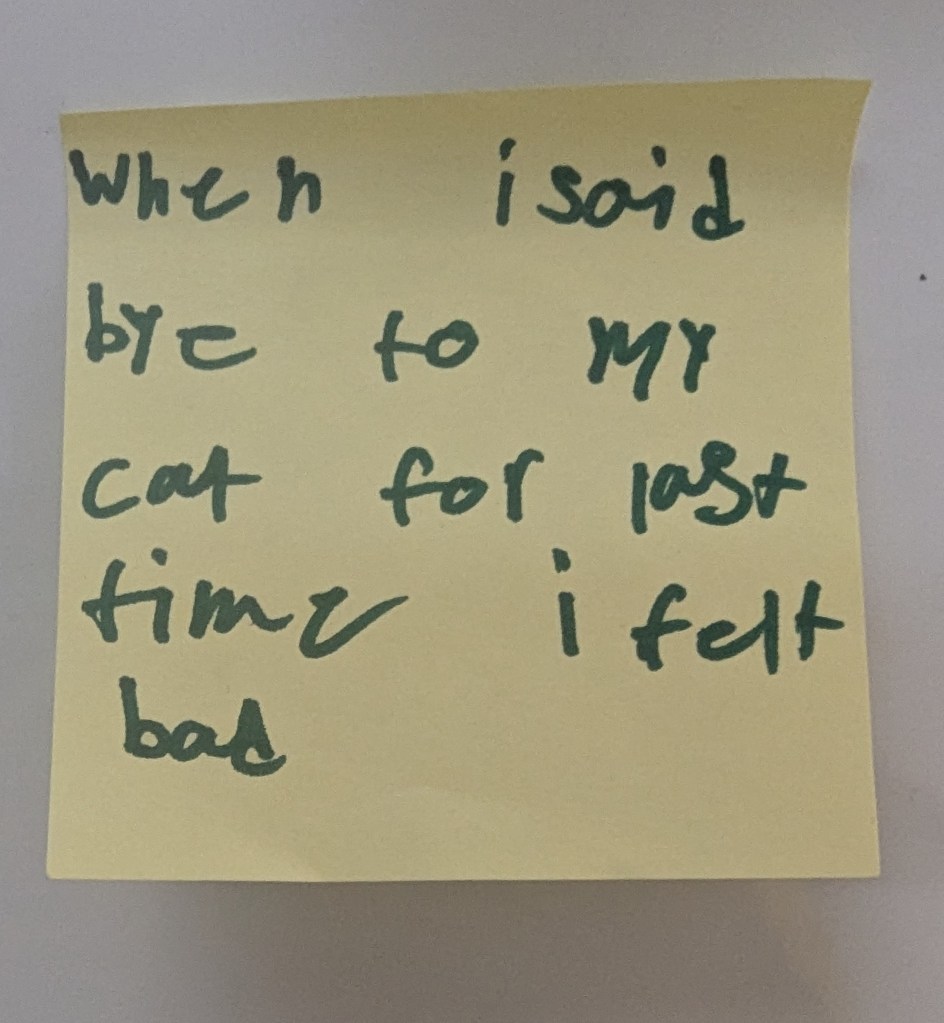

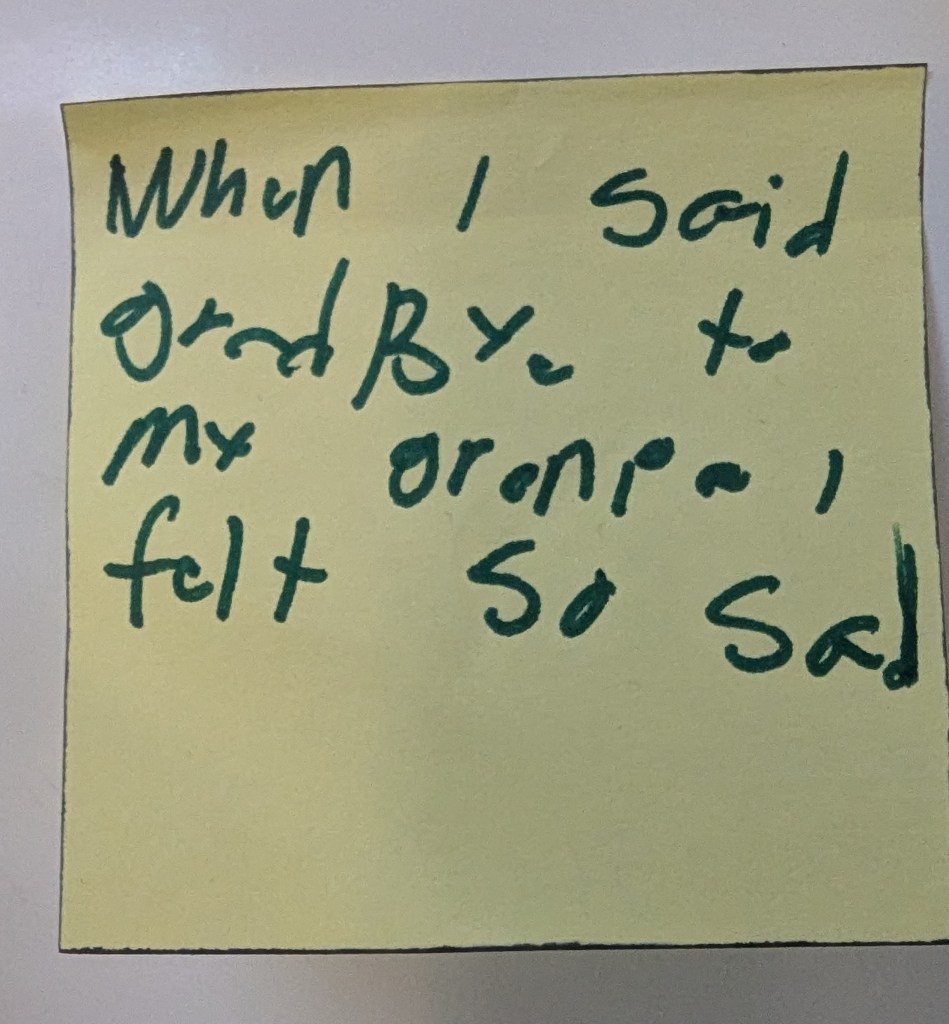

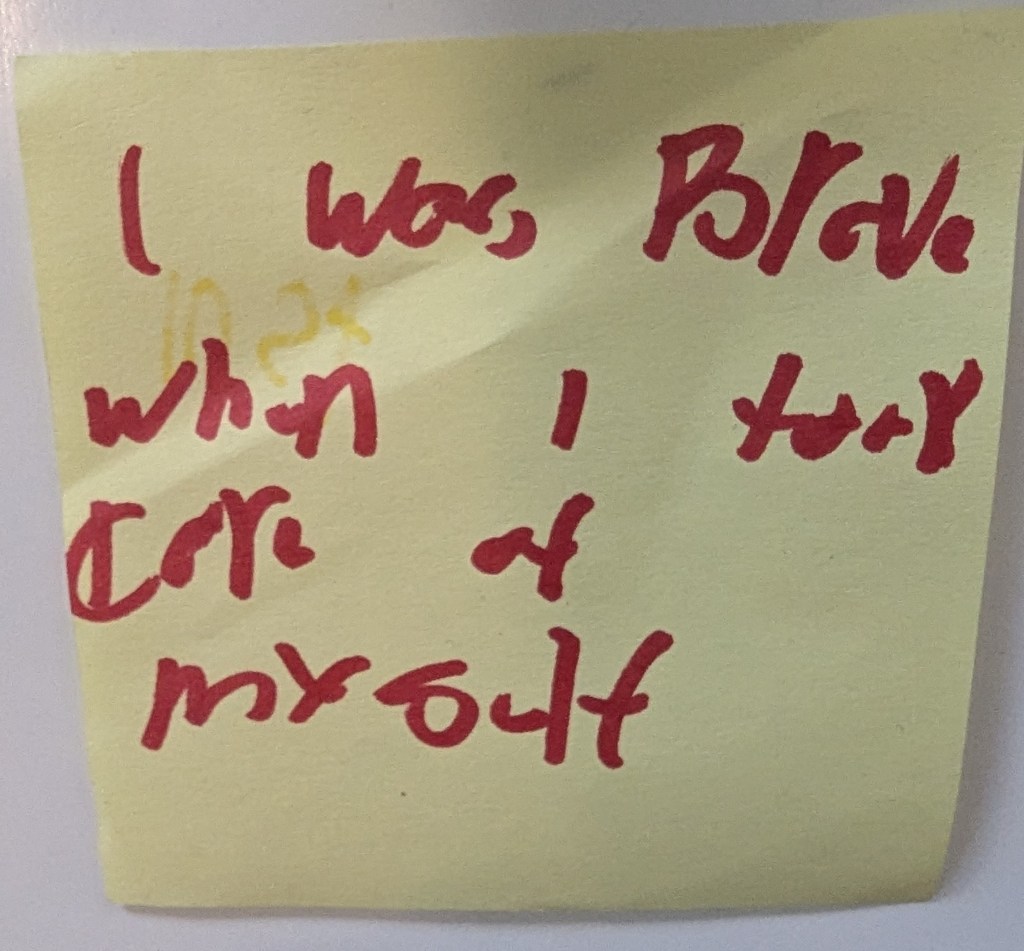

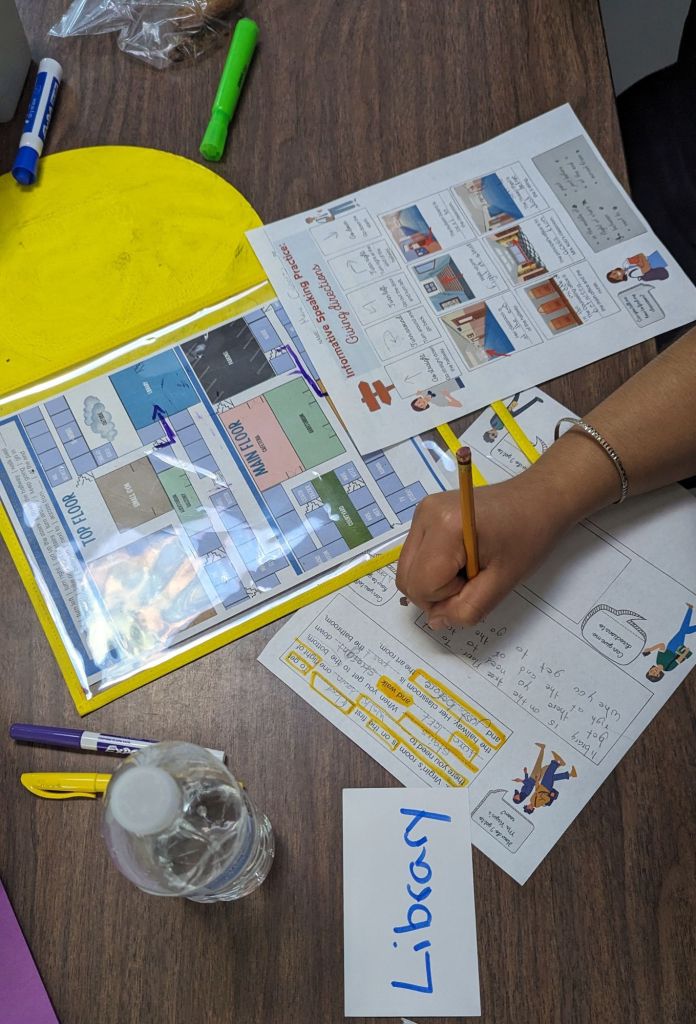

From here, Ebarvia moves on to discuss the importance of classroom community in Chapter 2, noting the potential growth that students can access when learning in a positive, safe, brave community. Aside from debunking the more traditional definition of what a “troublemaker” student would be, Ebarvia fills this chapter with tangible, realistic activities and strategies from her own public school classroom. She expands upon more known techniques (name tags, interviews, etc.) to provide opportunities to 1.) get to know students on deeper, more authentic levels, and 2.) support students of various identities, and various comfort levels when it comes to speaking their stories out loud.

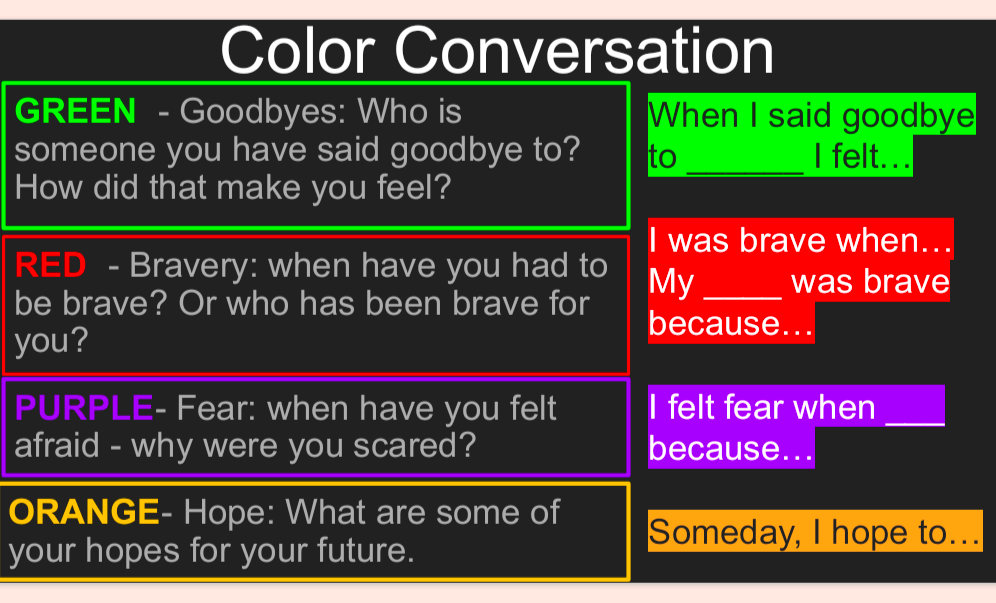

The middle section of the book moves beyond teachers’ experience and understanding of identity, and instead centers on students’ own understanding and support of both their own, and their classmates’, identities. Chapter 3 of Get Free focuses on methods for aiding students’ own understandings of identity, whereas Chapter 4 puts those understandings into action, providing strategies for fostering “critical conversations.” Ebarvia’s various frameworks provide students and teachers alike with tangible frameworks and processes within which everyone can be genuinely seen, heard, and respected.

For example, in a section regarding the support of LGBTQIA2S+ students, Ebarvia articulates the need for ALL teachers, regardless of content or identity, to understand modern language and definitions regarding sex and gender. After providing resources, she strikingly discusses how she discusses difficult identity-centered topics in her classroom, telling students that “How [they] respond today might be different from how [they] responded in the past or how [they] might respond in the future” (95). This ideology could be applied to so many topics, with the potential to create those truly brave spaces. With this mindset, students can understand that it is okay to be wrong about something, or to alter their opinion; changing, based on the acquisition of more knowledge and more experience, is not a bad thing.

Finally, the last two chapters offer an opportunity for expansion, offering strategies that encourage students to analyze such dynamics in their texts and, most importantly, in society at large. Ebarvia dives into biases here, explaining the importance of educators not only identifying them within themselves and their curriculum, but actually teaching students what various biases are, and how to identify them themselves. Extending from her Chapter 5 discussion of “reading against our biases”, Ebarvia’s final chapter urges the use of perspective-taking and perspective bending in order to encourage empathetic, less-biased reading. She continues her work with bias from the first few pages, now bringing students into the fold by asking them to identify dominant narratives, locate trends in how different identities show up as different types of characters, and more. Centering her curriculum around social justice standards serves as a helpful anchor to her work (218).

Key Take-Aways:

In even the title alone, Get Free, it is evident what Ebarvia’s core message seems to be: it is the duty of educators to use their presence in the classroom in order to guide students to view the world in way that is “more complicated, nuanced, [and] deepened”; good education “is empowering for all […] not necessarily in the same way, but in the ways each student needs” (226). To do this, carrying identity work throughout the year, and doing so extensively, is important; when it is incorporated only in the fall, it is harder to communicate its value. In Get Free, identity work is at the heart of everything, even literary analysis.

Ebarvia also asserts that changes within the current school systems are necessary in order to make such progress, and that such work is vital and urgent, especially given the current state of the world. In essence, “reimagining education” is needed, but it must truly move beyond “keeping the status quo” (292). Such a goal sounds daunting, even in its most bite-sized presentation. However, through her inclusion of anecdotes, strategies, and student reflection, Ebarvia presents a reality in which successful moves towards these goals are possible.

Within the brief epilogue, Ebarvia stresses her renewed understanding of the importance of the work she outlines throughout the book. In acknowledging how “the list of things to fight against is relentless,” Ebarvia argues for the persistent pursuit of education for liberation (293). After outlining experiences, reflections, and strategies across her previous chapters, Ebarvia remarks that the strong presence of hate and conflict in the world should not cause one to give up; rather, it should be all the more reason for educators to do all that they can to create more equitable education.

Text Usefulness:

As a high school teacher, the vast majority of the activities presented in Get Free are tailored to older students, mostly regarding the complexity of information and the critical thinking involved in many of the activities. However, one would imagine that many of the activities throughout, especially those presented in chapters two and three, could be easily adapted to middle school, or even elementary school, understanding of the concepts presented, as the goals of English Language Arts are fairly similar, even as one ages. If this work is indeed as vital as Ebarvia presents, then this book should not just be for high school educators. In fact, if students are expected to be able to maturely handle these conversations, then equity and curiosity needs to be presented as early as possible. For that reason, though focused more heavily on teaching older students, Get Free is an effective tool for educators of any level.

My Experience:

My biggest complaints with instructional guides is usually either that the students presented are “textbook students” –flat, overly simplified, inauthentic– and that the strategies seem unrealistic and/or pretentious. I’m thrilled that neither was the case with this book. Likely because of her real life experience with high school students, pretty much all of the activities presented seem attainable and effective. I already have multiple activities saved for use next fall. My only reservations surround potential community pushback, rather than the actual quality of the strategies. In fact, the only idea that I wish had been more prevalent is her experiences with any backlash, and what her thoughts are on the current climate of educator critiques.

Notably, I also really appreciate the use of anecdotes, for a variety of reasons. For one, though not a new concept, it is indeed much easier to understand and remember a concept when it is posed as a story. The variety and frequency of stories throughout the book made it easy to want to keep reading– something I find quite difficult with most textbooks. In addition, the use of anecdotes presented Ebarvia in a more human way. It is easy for textbook / instructional guide authors to come across as all-knowing, inaccessible, or even pretentious. Even with the inclusion of stories, authors sometimes –understandably – only choose their most shining moments. However, even in communicating her successes, Ebarvia is not gloating. Instead, she presents her worries, her struggles, her concerns, and her intentions. She even acknowledges what successes were born out of previous failures, a brave thing to do when presenting oneself in a position of authority. Reading Ebarvia’s book made me feel as though I was chatting with a department mentor, a welcome experience any time.

Overall, Ebarvia’s work offers a realistic insight regarding the current state of public education. To combat many current issues, Ebarvia provides strategies and activities for engaging students in meaningful, productive discussion, leading to the creation of a more authentic, effective schooling experience.

Heidi Fliegelman (she/her) is a high school English Language Arts teacher, an English graduate student at West Chester University, and a theatrical teaching artist and director in the PA area. Heidi’s work has been included in Voices from the Middle, English Journal, TEDxUniversityofDelaware 2021, and the National Council of Teachers of English. Having the opportunity to foster spaces of creativity, curiosity, and empathy is her favorite part about pursuing education.